Keith E. Williams and his family lost everything to the city of Detroit. Now, he wants it back.

Before his birth, Mr. William’s parents and older siblings left a once vibrant and predominantly Black neighborhood in Detroit, Black Bottom, as it was demolished by city officials since it was deemed part of a large-scale urban renewal project in the 1950s. Now, the area is a major freeway, I-375, and a place for mainly white and wealthy people, Lafayette Park neighborhood.

According to The Detroit Free Press, there is no confirmation to the city officials claim that the Black Detrioters were relocated successfully. Mr. Williams’s family was one of the 43,096 displaced residents and an additional 409 Black business owners, who found it difficult to rebuild their lives.

“It was taken from us,” said 64-year-old Mr. Williams, who is the chair of the state’s Black Democratic caucus. “It’s not only my family, it’s also all the other families that left too. We are still trying to catch up”, he added.

However, they may be getting closer to some relief now than in the past.

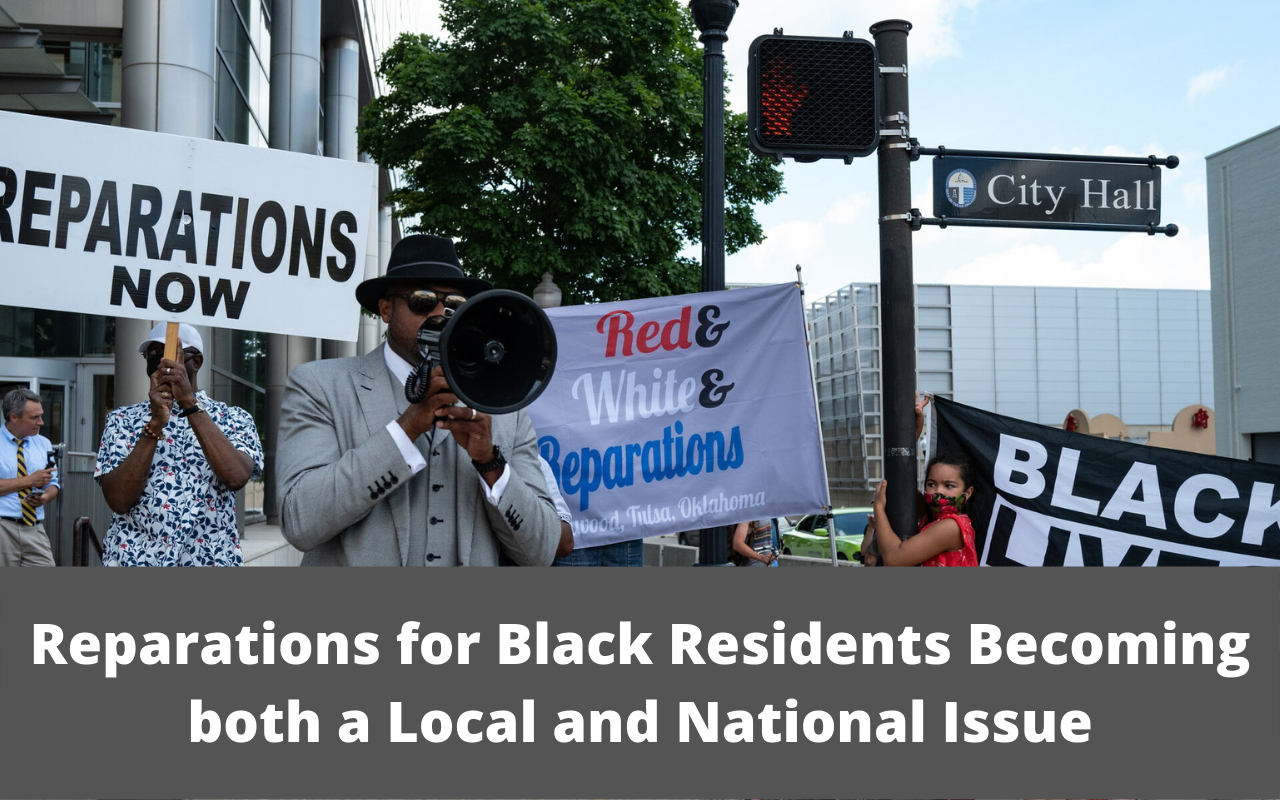

Detroit, like many other cities nationwide, is considering the best atonement for its racist past, part of a movement that is focused on the effects of slavery but has exptended to more local mishaps.

Detroit residents will be asked in November if they agree to the establishment of a reparations committee to study “housing and economic development programs” for Black individuals.

“It’s more than just talk for the first time,” said Mary Sheffield, the councilwoman who is leading the move after local community leaders like Mr. Williams contacted her. “We are seeing policymakers be serious about it, and we’re looking at what other cities have done, too.”

If a committee is created by Detroit, it will become part of a slowly increasing number of local and state governments considering, or introducing, reparations programs nationwide. In March, Evanston, Ill., a Chicago suburb, started to give $10 million worth of reparations to its Black residents in the form of housing grants. California became the frontrunner in creating a reparations task force in June.

Also in June, 11 American mayors pledged to introduce new programs for reparations for Black Americans in their respective cities, from big cities like Los Angeles to the small all-Black town of Tullahassee in Oklahoma.

According to the Mayors Organizing for Reparations and Equality founder, Mayor Eric Garcetti of Los Angeles, the coalition is planning to “double or even triple” its number of cities by the end of this year.

Mayor Quinton Lucas of Kansas City, Mo., shared that reparations seemed like “something that a lot of people said in 2020 to placate the masses.” He considers joining the coalition and introducing a pilot program in his city as something that lets local officials “match the rhetoric.”

“I think the mistake people sometimes make is that they think reparations is a story about slavery alone,” Mr. Lucas said. “But it’s about looking at the legacy of the unfairness that exists.”

According to Mayor Jorge Elzora of Providence, R.I., the reparations program could tackle the Black underrepresentation within “all the halls of power” in the city, such as in schools, businesses, and elected positions.

“As a country we have never addressed race issues directly, and look at where it has

Although these changes may sound new, there is a history of the movement behind it. In 1989, John Conyers Jr., a Democratic representative from Detroit, started to regularly reintroduce the same law suggesting the formation of a federal reparations committee, H.R. 40, until he retired in 2017. In 2019, congress finally heard the bill for the first time however, Mr. Conyers died the same year.

Read More: In The State of Florida, Quarantine Is Optional For Asymptomatic Students

Despite the failure of the bill, it was renewed in the 2020 presidential election as a major campaign concern to capture the attention of increasing young voters. After the peak of last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests, the national dialogue involving race revived the support of the reparations movement. In April, for the first time a House committee passed H.R. 40 and it is now on its way to the floor.

However, it’s still a long way before the bill gets approved by the legislators. If it gets finally approved, the amount of time it would take before a hypothetical commission could come up with recommendations and begin distributing aid is still uncertain.

Leave a Reply